How predictable is evolution?

- josiemcp

- Dec 6, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2021

Disclaimer: This is largely adapted from an essay I wrote in my final year of university and therefore some of the terms used may not be that accessible. That said, I am happy to explain anything in more detail.

Stephen Jay Gould once argued that, although impossible, replaying the tape of life would result in entirely different outcomes. Yet, there are abundant examples of evolution leading to convergent forms, and in some remarkable cases even convergently selected on the same proteins or genes in distantly related taxa. Here, I will define convergent adaptation as similar adaptive phenotypes that have arisen independently (Lee & Coop, 2019). The extent to which deterministic forces, whereby the same outcome is reached independent of starting conditions, as opposed to contingent forces, which depend on starting conditions and therefore have less repeatable effects, play a role in evolution is an ongoing debate in evolutionary biology. I will argue that evolution can be both deterministic and contingent, and understanding which factors bias the balance is now the more pressing question. I will make this by describing how convergent forms have arisen at the level of function, phenotype, enzyme pathway, protein, gene expression, and actual mutation, and for each discussing what factors promote convergence at a finer level. I will end with discussing how evolution can occasionally be unrepeatable and lead to unique events, and the reasons behind this.

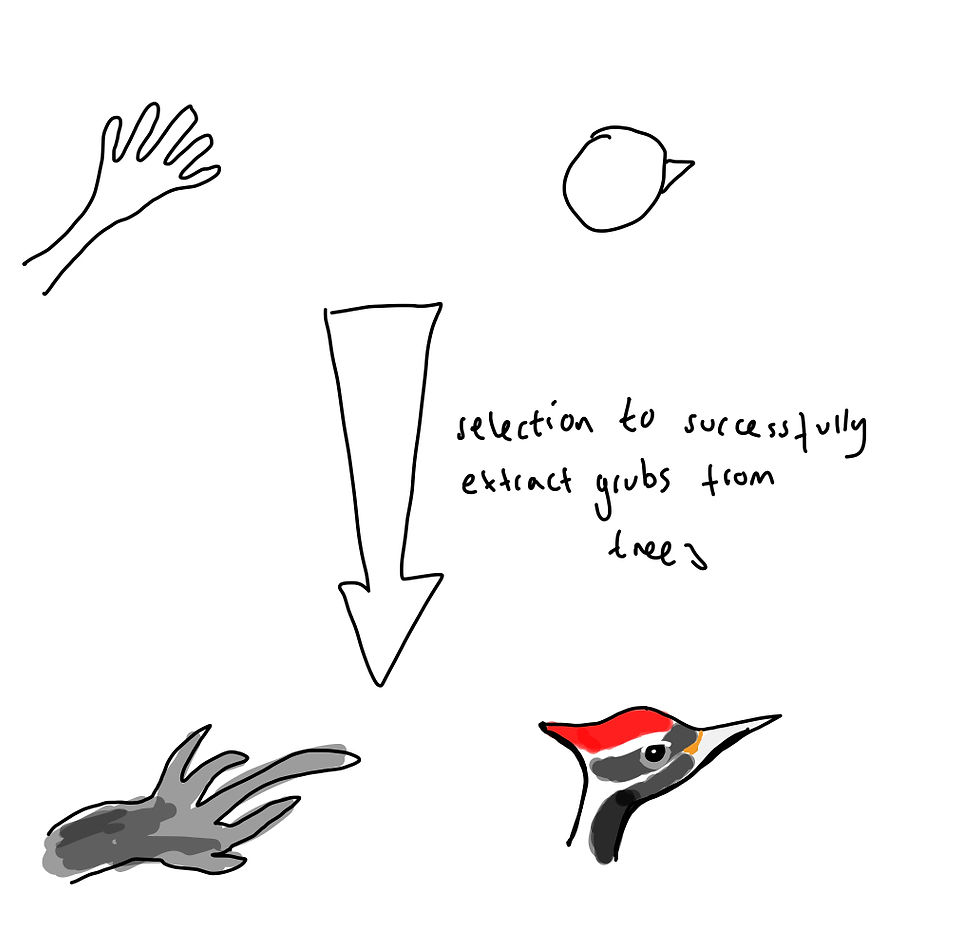

Evolution can favour traits that are functionally similar, but morphologically distinct. For example, the aye-aye and the woodpecker both fulfil a similar ecological niche, whereby they extract grubs from trees, and have both evolved a long penetrating structure to do so. However, in woodpeckers this structure is a beak and in aye-ayes it is a finger. This is attributable to the different legacies of their evolutionary histories. In other words, natural selection can by driven by similar conditions and the lead to the evolution of repeatable structures, but the form of these structures may be contingent on starting conditions.

However, evolution is often also repeatable at the morphological level, whereby organisms convergently evolve similar sturctures to fulfil similar niches. This is not necessarily underpinned by convergence at the genetic level. For example, two distinct forest mice populations have evolved improved tree-climbing behaviour mediated by longer tails, in the western population this is underpinned by a chromosomal inversion, but it is underpinned by entirely different QTL in the eastern population (Hager et al. 2021). This may reflect low levels of constraints at the genetic level. Barghi et al. 2020 showed how with redundant alleles, in different populations, the same trait was underpinned by different alleles.

Figure 1: A graph showing how when alleles are redundant, different populations will have the same trait underpinned by different alleles.

Additionally, the probability of convergent morphological adaptation holding at the genetic level appears to depend on how genetically divergent populations are. A recent study on parallel adaptation to alpine environments in Arabidopsis demonstrated that genetic divergence is an important predictor of convergence at the genetic level, likely because more closely related species are more likely to share the same genetic variants (Bohutínská et al. 2021).

Similarly, in African cichlid fish Astatotilapia burtoni the level of parralleism at the phenotypic and genetic level was greater in populations with more closely related ancestors. It this case there was also a negative correlation between levels of shared genetic variation and parallelism, suggesting that it is sharing these genetic variants that promotes parallelism. In all, repeatedly in morphological evolution can occur independently of convergence at the genetic level, and this is likely modulated by how redundant the genes underpinning the trait are and how genetically divergence the populations are.

Repeated evolution of a trait can repeatedly select on the same enzyme pathway. In three distantly related electric fish, the insulin growth factor pathway is implicated in producing electric organs. This is likely because this pathway is important in increasing organ size, which is necessary for electric organs (Gallant et al. 2014) and has been described as the ‘only one way to make an electric organ’. This supports the previous assertion that when one or limited subset of genes that can lead to required function, or genes are less redundant, convergence holds at finer levels.

Furthermore, the same position within an enzyme pathway can be convergently selected on. The first enzyme in the melanism synthesis pathway underpins albinism in planthoppers and cavefish. Bilandzija et al. 2012 suggested a number of reasons this might be. Primarily, the OCA2 gene that underpins this enzyme is large (~345KB), therefore there are increased positions where mutations can occur, increasing the probability of a single mutation occurring. Secondly, the blocking of this enzyme may be advantageous in that it has been shown to lead to accumulation of L-tyrosine, which have been suggested to aid other adaptive processes, such as the synthesis of catecholamines. Alternatively, or additionally, it could be the least disadvantageous place to block. The later enzymes in the pathway have been shown have pleiotropic roles in immune function, and therefore changes in them may be selected against. In all, evolution may occur repeatedly at the same enzyme due to mutational target size, increased advantageous side-effects and less disadvantageous side-effects.

Evolution can be repeatable at level of changed gene expression. The evolution of pregnancy necessitates an ability to withstand foreign signatures of proteins normally be rejected by the immune system. Roth et al. 2020 identified 116 genes that convergently change expression during mammalian female pregnancy and male pipefish Syngnathus typhe pregnancy, including a downregulation of the immune MHC1 pathway. It has been argued that changes in gene expression, particularly by changes in cis-regulatory elements, are more likely to govern evolution, and therefore may be more likely to be convergently expressed. This is because they are thought to be more modular than protein-coding genes, in that they can affect the expression of one genes without impacting its other functions. In all, changes in gene expression may repeatedly govern evolution, perhaps due to their reduced pleiotropy.

Evolution can even be repeatable at the level of the mutation. A particularly topical example is that one US laboratory found seven genetically independent COVID-19 lineages that had acquired a mutation in the same place on the virus spike protein, in six of these lineages this change was from glutamine to histidine amino acids (Cooper, 2021). The repeated changes in the targeting of the spike protein is likely due to a selective advantage in survival. The convergence of the same mutation may be due to genetic factors influencing mutational hotspots. For example, transitions (changes between pyrimidine bases (C&T) and purine bases (A&G) are more likely to occur than transversions (conversion of a pyrimidine to a purine). In 389 convergent events in natural and laboratory populations there was a 4-7-fold excess of transitions (Stolzfus & McCandlish, 2017). Additionally, CpG is a mutational hotspot in mammals and birds due to, among other reasons, the effects of methylation damage and repair (Smeds et al. 2016). In experimental evolution, mutation bias has been shown to influence the trajectory of adaptive evolution (Storz et al., 2019). In all, genetics factors can make evolution repeatable, even to the level of the mutation.

All that said, evolutionary one-off events perhaps suggest that evolution is not fully repeatable. Heliconius butterflies are unique among the ~18,000 described butterflies in their pollen-feeding behaviour. This provides them with a rare source of amino acids throughout adulthood, and seems to allow them to reproduce for markedly longer (Dunlap-Pianka et al. 1977). It is therefore surprising that no other butterflies have evolved this behaviour, but this can perhaps be explained by requirements of pre-adaptations to favour the evolution of pollen-feeding (Young & Montgomery 2020). Heliconius are toxic, which reduces predation, allowing longer lifespans, perhaps favouring extended investment into reproduction. They also have home-ranges and invest more into learning, which may be necessary for memory of pollen-rich resources. Again, the benefits of memory are likely dependent on lifespans long enough to reap the rewards. Finally, they have a cocoonase gene duplication, which is upregulated in their mouthparts (Smith et al., 2016). Cocoonase is a protease utilised by moths to escape cocoons. Heliconius lack cocoons, therefore it is hypothesised these genes may have been co-opted for pollen digestion. The gene duplication potentially allowed the biochemical processing of pollen to evolve without constraints. In other words, perhaps the unique evolution of pollen-feeding in Heliconius butterflies is contingent on prior-adaptations for long life and genetic factors. The interdependences between these traits could be resolves using agent-based models. In all, unique evolutionary events, reveal that evolution is not completely repeatable.

In conclusion, evolution will likely never be fully predictable, it is a complex process and traits likely show complicated interdependencies that can affect evolution in complex and fascinating ways, as seen by evolutionary one-offs. Nonetheless, it seems that there are factors that promote predictability. Natural selection by virtue of being a deterministic source will largely lead to organisms matched to their environment. This can lead to the evolution of similar structures in different organisms, however the form of these structures will be, to an extent, contingent on starting conditions. These structures can even be underpinned by the same proteins or genes. Whether this is the case will be modulated by the number of ways a trait can be genetically underpinned, how the genes influence other processes and properties of the gene themselves. Understanding how and when we can predict evolution will have wide-ranging consequences, as the current pandemic demonstrates.

Comments